Mutation testing systems, improving the quality of tests

Professionally I label myself as a developer, although I don’t like labels very much and I prefer to say that the reason for my work is: to create quality software. But what is quality software? I like to define it as follows:

Quality software is that which meets the user’s needs efficiently and without errors.

I could add more adjectives, go into detail why needs and not requirements… but for me, that would be the definition. However, it’s difficult to get quality software if it’s not written with quality code.

Quality software → quality code

Fortunately, developers are not alone in this task. There are tools for static code analysis (Checkstyle, PMD, FindBugs, SonarQube…) and different recommendations for good practices (personally I would highlight Clean Code and The Pragmatic Programmer). And there among proposals, acronyms and metrics, there’s no developer that doesn’t directly associate the term quality with the term testing (right?)

Quality code → quality tests

Testing: the path to quality

Tests are as important to the health of a project as the production code is.

Clean Code. Chapter 9: Unit Tests

There are several types of tests (unit, integration, acceptance…). The most widespread are unit tests and integration tests. With them you get a certain perception of security, since although we do not know if the code does what it should, at least it does what it says.

But is this so? Paradoxically, this practice consists of generating more code. So we continue programming, but who says this code does what it says? That is, who watches over the quality of the tests? Again another association of terms: quality tests are those that offer a high % of code coverage.

Quality tests → High % coverage of our code

A higher percentage of code coverage gives better tests and more reliable code. This is nothing new. If I talk from my personal experience, a few years ago (back in the early 2000s) the minimum % coverage requirement was part of the delivery specifications of some projects. “This deliverable must have a battery of tests that ensure a minimum of 70% code coverage”, as a synonym of error-free code and proven quality in at least 70% of the code.

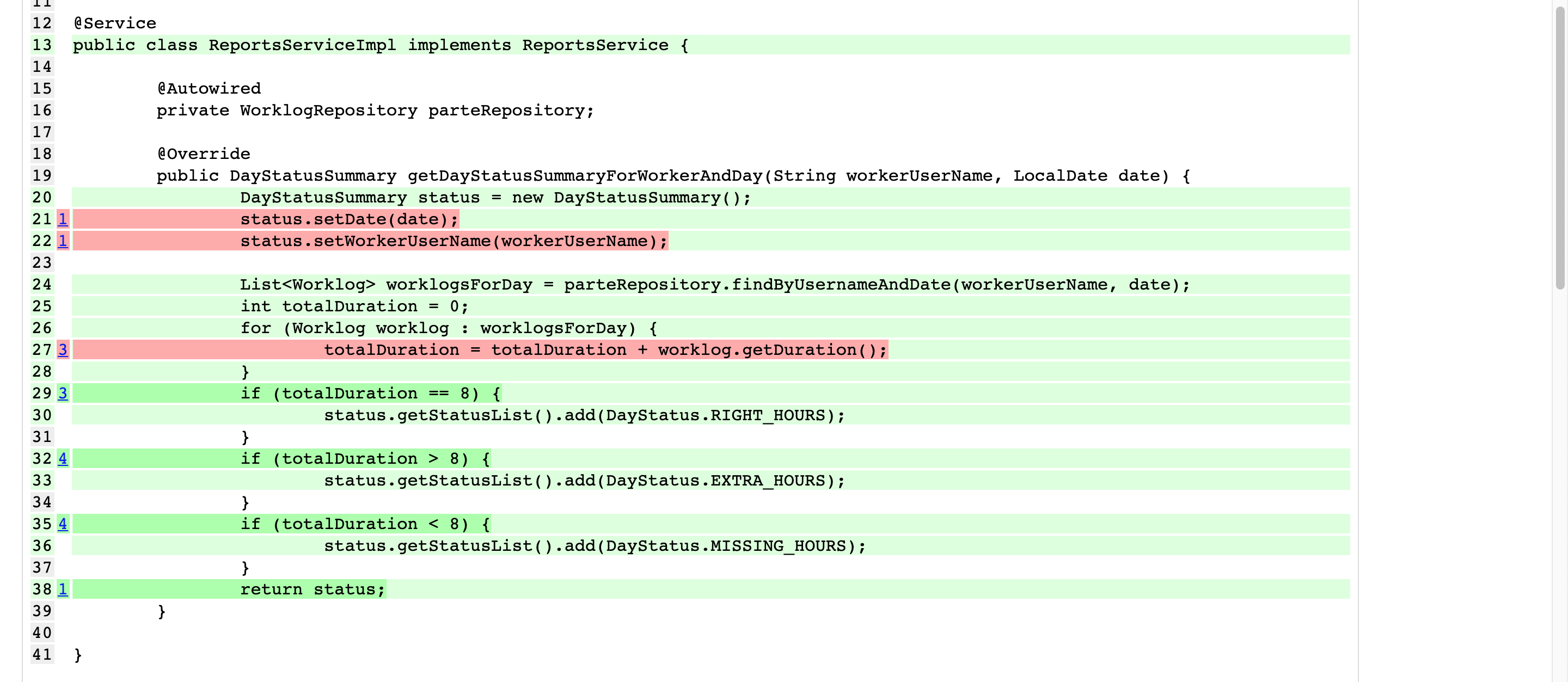

Taking as an example an application to check the hours (or part hours) worked, let’s imagine that we are developing a method that, given a worker and a day, checks the status of the worker’s time sheets on that day (whether or not he has done the required hours, if he has done extra time….).

ReportsServiceImpl.java see all

@Override

public DayStatusSummary getDayStatusSummaryForWorkerAndDay(String workerUserName, LocalDate date) {

DayStatusSummary status = new DayStatusSummary();

status.setDate(date);

status.setWorkerUserName(workerUserName);

List<Worklog> worklogsForDay = worklogRepository.findByUsernameAndDate(workerUserName, date);

int totalDuration = 0;

for (Worklog worklog : worklogsForDay) {

totalDuration = totalDuration + worklog.getDuration();

}

if (totalDuration == 8) {

status.getStatusList().add(DayStatus.RIGHT_HOURS);

}

if (totalDuration > 8) {

status.getStatusList().add(DayStatus.EXTRA_HOURS);

}

if (totalDuration < 8) {

status.getStatusList().add(DayStatus.MISSING_HOURS);

}

return status;

}

Let’s see an example of tests that we submitted at the time:

GetDayStatusSummaryForWorkerAndDayTests.java see all

@Test

public void get_status_summary_for_worker_and_day() {

reportsService.getDayStatusSummaryForWorkerAndDay("USU", LocalDate.now());

assertTrue(true);

}

@Test

public void calculates_the_status_based_on_worker_and_date_worklogs() {

List<Worklog> partes = new ArrayList<Worklog>();

Worklog wl = new Worklog();

wl.setFromTime(LocalTime.of(8,0,0));

wl.setToTime(LocalTime.of(19,0,0));

partes.add(wl);

Mockito.when(worklogRepository.findByUsernameAndDate(ArgumentMatchers.anyString(), ArgumentMatchers.any(LocalDate.class))).thenReturn(partes);

LocalDate fecha = LocalDate.now();

reportsService.getDayStatusSummaryForWorkerAndDay("USU", fecha);

Mockito.verify(worklogRepository).findByUsernameAndDate("USU", fecha);

}

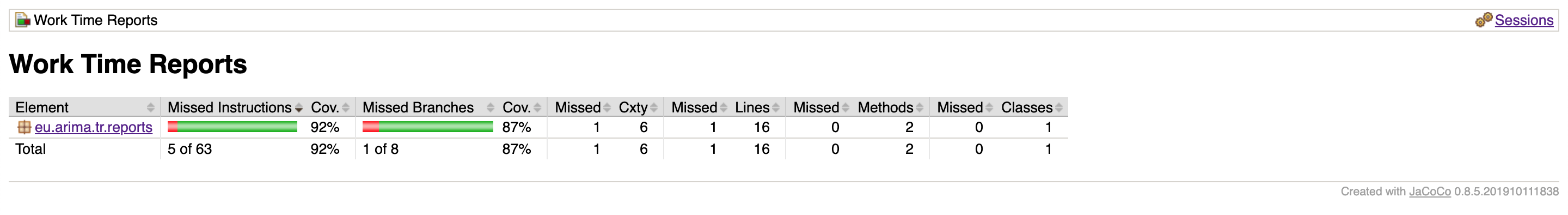

We configured JaCoCo to get the test coverage report and the result is as follows.

We have a coverage of 92% of lines and 87% of branches: objective met. But…if you look: the first test will (almost) never fail because it always ends with assert true, the second is a bit “more complete” because at least it verifies that the hours (or part hours) are retrieved… 1

Well this was my reality, and I am very much afraid that it was THE reality of that time in many projects (and who knows if in some of today). The projects met the code coverage requirements, which was far from having quality software.

It’s true that the example I have given is extreme, but it is real. In my opinion, the problem is in the focus: everything has been turned around and the tests are created as a mere tool to fulfill one of the requirements of the project.

minimum % coverage required → test = “waste of time”

Let’s go back to the original approach. It would remain:

Quality software → quality code → quality tests → % coverage of code

In this scenario, the tests are created under the premise of having a higher quality code and the % coverage becomes another indicator. We are going to see a fragment of a better test example, one of those we do out of conviction and not just to fulfill a requirement (I suppose that they are more similar to those that we can find in current projects than previous ones …).

GetDayStatusSummaryForWorkerAndDayTests.java see all

@Test

public void if_the_worklog_for_the_resquested_day_is_less_than_8_hours_the_status_is_MISSING_HOURS() {

Worklog worklog = Mockito.mock(Worklog.class);

Mockito.when(worklog.getDuration()).thenReturn(7);

Mockito.when(worklogRepository.findByUsernameAndDate(ArgumentMatchers.anyString(), ArgumentMatchers.any(LocalDate.class))).thenReturn(Arrays.asList(worklog));

DayStatusSummary resultado = reportsService.getDayStatusSummaryForWorkerAndDay("USU", LocalDate.now());

assertEquals(DayStatus.MISSING_HOURS, resultado.getStatusList().get(0));

}

@Test

public void if_the_worklog_for_the_resquested_day_is_equal_to_8_hours_the_status_is_RIGHT_HOURS() {

Worklog worklog = Mockito.mock(Worklog.class);

Mockito.when(worklog.getDuration()).thenReturn(8);

Mockito.when(worklogRepository.findByUsernameAndDate(ArgumentMatchers.anyString(), ArgumentMatchers.any(LocalDate.class))).thenReturn(Arrays.asList(worklog));

DayStatusSummary resultado = reportsService.getDayStatusSummaryForWorkerAndDay("USU", LocalDate.now());

assertEquals(DayStatus.RIGHT_HOURS, resultado.getStatusList().get(0));

}

@Test

public void if_the_worklog_for_the_resquested_day_is_more_than_8_hours_the_status_is_EXTRA_HOURS() {

Worklog worklog = Mockito.mock(Worklog.class);

Mockito.when(worklog.getDuration()).thenReturn(10);

Mockito.when(worklogRepository.findByUsernameAndDate(ArgumentMatchers.anyString(), ArgumentMatchers.any(LocalDate.class))).thenReturn(Arrays.asList(worklog));

DayStatusSummary resultado = reportsService.getDayStatusSummaryForWorkerAndDay("USU", LocalDate.now());

assertEquals(DayStatus.EXTRA_HOURS, resultado.getStatusList().get(0));

}

In this case the coverage percentage is 100% of code lines and branches. And it also seems that the tests already make more sense. Now, yes, we would feel safe with them, right? Is that so, or is it just a perception?

If someone modified part of the method, of course, before committing and pushing, it would pass the tests. If there were no tests in red, all clear: nothing has been “broken”.

Can we be sure?

Let’s suppose that what is modified in the example method is:

ReportsServiceImpl.java

for (Worklog worklog : worklogsForDay) {

totalDuration = totalDuration + worklog.getDuration();

}

for

for (Worklog worklog : worklogsForDay) {

totalDuration = worklog.getDuration();

}

Our tests will continue to pass2. We also continue with a high % coverage… Everything is perfect!

Test → feeling of security

Mutation testing systems: securing the way

Because we can’t write perfect software, it follows that we can’t write perfect test software either. We need to test the tests.

The Pragmatic Programmer. Chapter 8: Pragmatic projects

It seems that the tests we have created are not as good as we thought, they don’t have enough quality to ensure the quality (forgive the repetition) of our method. We have been offered a false sense of security.

It’s clear that achieving a high % coverage isn’t easy and if writing tests is costly, writing good tests is even more so, and what we get is an unreal sense of security. Couldn’t we make this feeling closer to reality? Couldn’t we detect situations, like the one we’ve seen, automatically?

Well, to deal with this type of situation, the so-called Mutation Testing Systems come up. The idea behind them is none other than the one we have put forward in the last example: to simulate changes in the source code being tested and verify that in reality, some tests are failed after a modification has been made.

Quality software → quality code → quality tests → mutation test % coverage

The basic concepts are as follows:

- Every change that is generated in the code is a mutant.

- Each change (or mutation) that our tests are able to detect is called killing a mutant (killed mutant).

- Any changes (or mutants) that our tests are not able to detect are living mutants (survived mutant).

- Changes in the code are generated by mutant operators (mutators / mutation operators), which are grouped into different categories depending on the type of change they make in the code.

Personally, I hadn’t heard of this concept until relatively recently. However, the reality is that it has been with us for several years. There are alternatives for the different technological stacks, for example:

- Stryker for JavaScript, TypeScript, C# and Scala

- Mutode for JavaScript and Node.js

- Cosmic Ray for Python

- mutmut for Python

- Mutant for Ruby

Back to Java, some of the mutation systems are (or have been):

We have used PIT because:

- It is easy to use

- It is easily integrated in the projects that we have used (through a maven plugin) as well as in the IDE (in our case Eclipse)

- It supports different configurations (some to improve efficiency)

- It is still active

- It seems to be the most widely used solution today

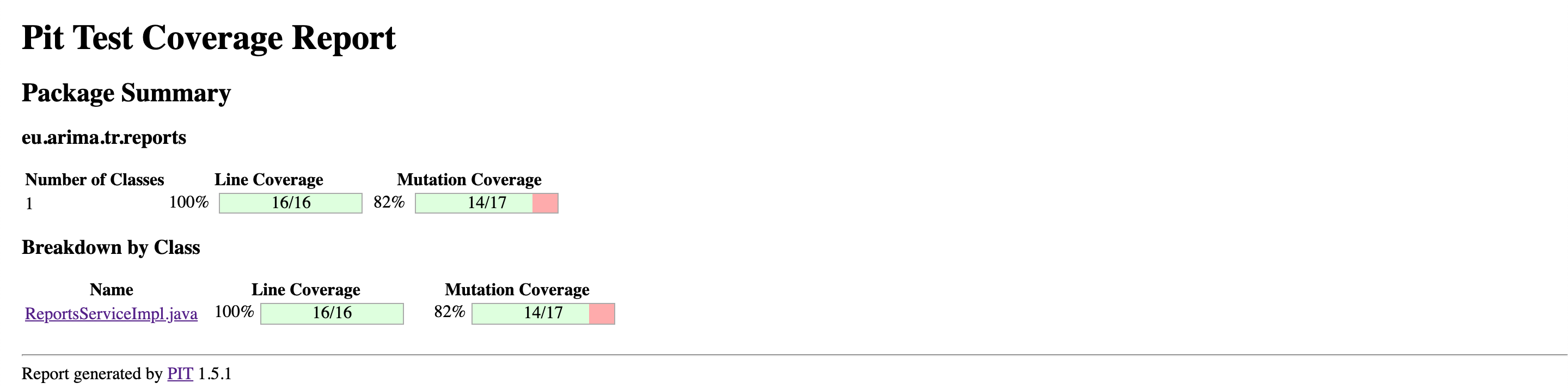

If we run the pitest report in our example, we will see this result.

Here we see general result: on one side is the coverage of code lines, and on the other side, the mutation coverage.

The lines marked in green reflect code in which PIT has made changes and tests have been able to detect them. The lines marked in red reflect the lines of code in which our tests have failed to detect that there had been changes. If we look at line 27, it is the one that we had modified and it passed our tests. Now we have two options: go ahead, accepting that our code may have some fragility, or the most accurate (and logical), add/correct tests that ensure reliability when faced with detected changes.

In the following link the sample code which we have worked on is available, where we have improved the tests to achieve greater mutant coverage.

The mutants that are applied are configurable, and the balance between the number/type of mutants configured and the execution time must be assessed. The greater the number of tests, the greater the number of lines of code and the greater the number of mutants, the more time Pit will need to generate the corresponding report. We could reach a point where it is so costly to do the report that we skip it, and then all the effort put into testing would be lost. In the examples, we have seen only unit tests, but the same applies to integration tests (many of them already costly in themselves).

In our case, we usually configure the ones that come by default (DEFAULTS) and add those of the following group (NEW_DEFAULTS). In the sample code, others are configured, but here the Pit mutators are shown, so try to change the configuration and see the different results.

Conclusions

Quality software → quality code → quality tests

Quality software requires quality code, which in turn can be ensured thanks to quality tests.

Generally, there is more code to test a method than to implement it, which obviously involves a lot of time: we will spend more time testing a method than implementing it. We need to ensure that this effort is not in vain.

Mutation testing is a tool that allows us to evaluate and improve the quality of our tests. The price to pay is the increase in time needed to do it. Taking into account that it is based on code mutations and that it applies not only to unit tests, but also to integration tests, as the code grows and the number of tests increases, it will take longer to execute them. Therefore, it is necessary to look for formulas that ensure that at some stage of our development, all tests are done: if we stop doing them because it is too costly, all the effort will have been for nothing.

We have taken a firm step, but we are still on the path to quality: what can we do to find this balance? Can we organize the tests in some way to make things easier? Are there tools that allow us to develop/run tests more efficiently?